Texas’ SB4 Law: Balancing Immigration Enforcement With Fiscal Realities

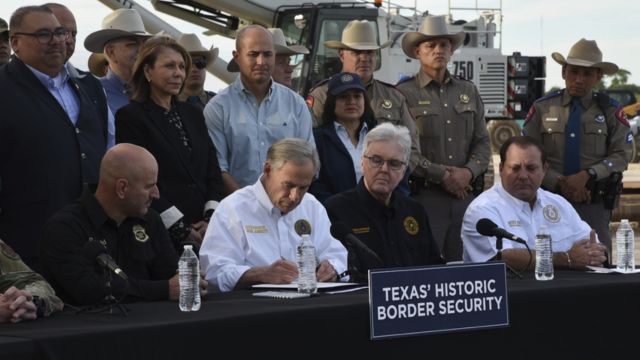

Texas’ exploration into immigration enforcement is on pause as it works its way through federal courts.

SB4 allows state and local authorities to arrest anyone suspected of illegally entering the United States. It makes unauthorized entry into the United States a state crime, punished initially as a misdemeanor and, for repeat offenders, as a felony.

The concern for a rural county in West Texas, whose leaders support the bill, is how much enforcement will cost.

Terrell County has a population of less than a thousand people, but it is Texas’ tenth largest county by land mass. It is located adjacent to Big Bend National Park and shares a border of approximately 50 miles with Mexico. It features vast open expanses, stunning canyons, and acres of scrub vegetation. A hiker can throw a stone across the Rio Grande, the natural border between the United States and Mexico.

Sheriff Thaddeus Cleveland worked as a US Border Patrol agent for almost two decades before transitioning to local law enforcement.

The sheriff claims there is little crime in Terrell County, but he wants the new arrest powers afforded by SB4. He believes unrestricted immigration is still a concern with a significant impact on Terrell County. He monitors nearly all of his county’s 2,300 square miles daily.

“I tell people this area is the roughest, toughest most unforgiving portion of the U.S.-Mexico border,” Cleveland added.

The area is primarily desert and is difficult for migrants to navigate. Those who do are typically seasonal laborers seeking to enter the country without being inspected.

“We don’t have anyone looking to surrender for asylum or other political reasons. We encounter folks who seek to cross the border illegally. Many of them are looking for jobs, such as picking strawberries in Santa Maria, California,” Cleveland noted.

Regardless of motivations, economic or not, good or evil, Cleveland is concerned about the security of his home county and advocates for more stringent state immigration legislation.

Currently, he has the authority to detain migrants who are trespassing on private land or in smuggler cars.

According to Cleveland, his office was able to apprehend approximately 10 persons per day crossing illegally in 2023 with his present authority. The number of persons crossing in far-flung Terrell County pales in comparison to other regions of the southwest border, but the sheriff remains concerned.

“They hope to slip into the United States and then travel north undetected. If they are discovered and encountered in the desert, they usually flee or abduct. And if we stop them on the interstate, it usually leads into a high-speed automobile chase,” Cleveland explained.

Under SB4, he and his deputies can interrogate people about their citizenship during regular interactions, such as a traffic check, and arrest them if they believe they are here illegally.

The statute was briefly in effect on March 21 due to judicial wrangling, but the sheriff claims no one was arrested during those nine hours.

The measure is on hold because the US Department of Justice has sued, claiming SB4 is unconstitutional. In court documents, the DOJ claims that Texas is violating the federal government’s sole jurisdiction to enforce the country’s immigration laws.

Cleveland, who has worked for the US Border Patrol for over two decades, sees the law as an opportunity to assist federal authorities. He is concerned about how to implement it and how his county would pay for it.

“I support it, but there are some questions that are left to be answered as far as some of that funding for resources,” the mayor of Cleveland remarked.

The county jail can house seven persons and does not have separate quarters for male and female inmates. Terrell County has only five law enforcement officers, including the sheriff, patrolling about 2,300 square miles of terrain. County Judge Dale Carruthers, who is also a strong proponent of SB4, told Scripps News that the county budget is only $1.8 million, which covers everything from police to schools and roads.

“We’re financially strapped,” Carruthers remarked. “You know, anything else that would be an unfunded mandate could cripple this county.” She said that Texas’ border security effort, known as Operation Lone Star, provides a key lifeline for her area, particularly law enforcement. It has funded the addition of two sheriff’s deputies.

However, there are additional costs: transportation of possible migrant arrests from the county to larger facilities, as well as lawyers to pursue state crimes and public defenders for migrants in local courts. Operation Lone Star has expended significant resources in this area of Texas, particularly for the prosecution of state offenses against migrants who have crossed into the United States.

If the new law goes into force first, it will make it a misdemeanor for a migrant to enter the nation illegally and a felony if he or she repeats the violation, punishable by up to 20 years in jail.

Once detained, travelers might either comply with a Texas judge’s order to leave the country or face misdemeanor charges of illegal entry. Furthermore, the rule states that migrants must be sent to ports of entry along the US-Mexico border, even if they are not Mexican citizens. Migrants who refuse to leave could be arrested again on more serious felony charges.

Texas has contended in court that the statute is consistent with the US government’s immigration enforcement, while the Justice Department has stated that it is a clear breach of federal jurisdiction and would cause border instability. The Mexican government has also expressed objection to the state law, saying it will not accept any migrants that Texas attempts to deport back across the border.