Senator Padilla Advocates for Immigrant Populations Amid Immigration Debate

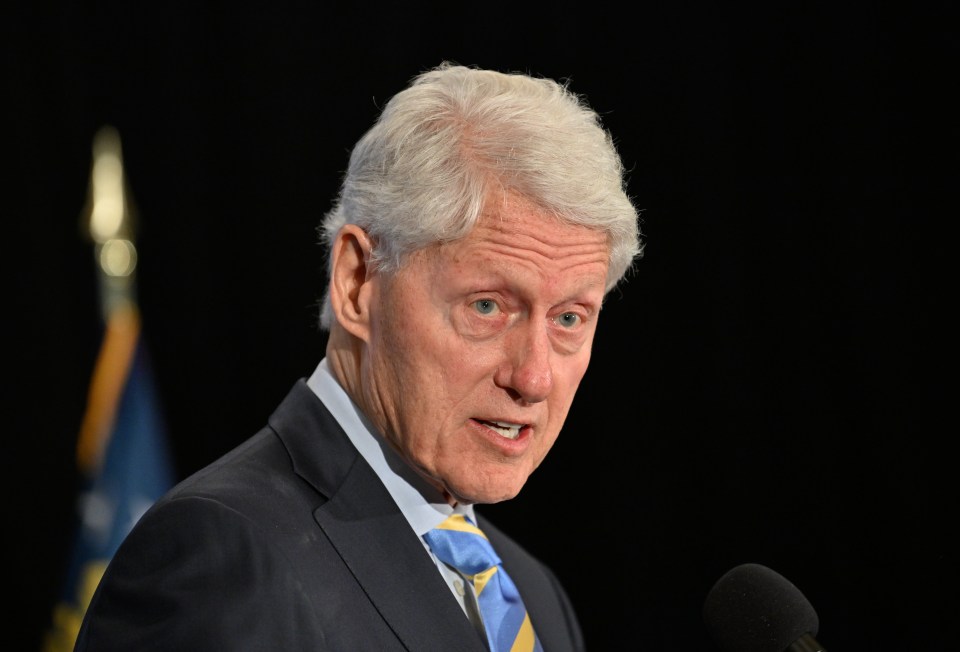

“Is it true?” Biden questioned Sen. Alex Padilla, referring to the approximately 25% of Latino kids in kindergarten through high school in the United States. Padilla said the query came when he was waiting with the president in a back room of a library in Culver City, California, for an event in February.

Padilla had hoped for this kind of breakthrough with the Democratic president. Biden was debating his reelection campaign, executive actions on immigration, and what to do about a southern border marked by unprecedented levels of illegal crossings throughout his term.

Padilla wanted to make sure Biden considered the potential of the country’s immigrants. “Mr. President, do you know what I call them, those students?” Padilla recalls saying. “It’s the workforce of tomorrow.”

It was just one of many times Padilla, 52, the senior senator of California, has used the opportunity — from face-to-face meetings with the president to regular calls with top White House staff and sometimes outspoken criticism — to stamp his mark on the Democratic Party’s immigration policy.

Padilla, the son of Mexican immigrants and the first Latino to serve his state in the Senate, has emerged as a steadfast presence at a time when Democrats are increasingly focused on border security and the country’s immigration policy is unsettled.

Illegal immigration is viewed as a rising electoral dilemma for Democrats, as officials at the border and in towns around the country have struggled to handle recent surges. In addition, dissatisfaction with Biden may be causing the party to lose popularity with Hispanic voters. However, in a series of interviews with The Associated Press, Padilla revealed a deep reserve of optimism about his party’s capacity to gain support from and benefit immigrant populations.

“Do not be scared or reluctant to discuss immigration. “Lean into it,” Padilla said. “First and foremost, it is the morally correct thing to do. Second, it is critical to the strength, security, and destiny of our country.”

Even as immigration politics get more contentious, the senator has attempted to tether his fellow Democrats to that approach. Donald Trump, the likely Republican presidential nominee, has said that illegal immigrants are “poisoning the blood” of the country, accusing Biden of enabling a “bloodbath” at the southern border. Meanwhile, Biden’s policies and language have swung to the right at times, as illegal border crossings become a liability in his reelection campaign.

During his State of the Union address, Biden engaged in an unscripted exchange with Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, a Republican from Georgia, in which he referred to a Venezuelan man accused of killing a nursing student in Georgia as a “illegal” — a term frowned upon by immigration rights advocates.

Padilla talked about the speech with Rep. Tony Cárdenas in their Washington residence afterward. The men, who have known each other since their early days in Los Angeles politics, have formed a political odd pair while separated from their families in California. Padilla’s height towering over many in the Capitol, and he normally talks in measured tones, but Cárdenas, who is lower in size, has been known to cry during debates and frets that his voice may carry into the nearby apartment.

“Usually I’m talking in 20 sentences by the time he’ll get his one or two sentences,” Cárdenas was quoted as saying. “He’ll say what I’m saying pretty much, but much more calmly, much more methodically.”

That night, Cárdenas claimed, they discussed how they wanted politicians to avoid identifying migrants as “illegals” since it denied them of dignity.

Padilla informed him he’d phone the White House.

“He’s is the kind of person who steps in and steps up, and, you know, he’s tactical about it,” he remarked.

It’s a challenging job to play, especially as Democrats attempt to shore up what is perceived as a weakness in border security in the key states that will determine control of the White House and Congress.

Even in California, Republicans have been emboldened on immigration as they seek to reclaim statewide significance, according to Mark Meuser, a lawyer who lost campaigns to Padilla for Senate in 2022 and California Secretary of State in 2018. He claimed that leading California Democrats like Padilla “are driving hard towards the extreme edges of their party.”

Padilla has pushed the president and other Democrats to maintain their position that border enforcement measures be accompanied by improvements for existing immigrants. Padilla voiced anger with how certain Democrats, including Biden, failed to maintain immigration changes, such as a road to citizenship for people who entered the country illegally as children, which was a primary priority during a border security agreement earlier this year with Senate Republicans.

During those negotiations, Padilla established himself as the leader of the left’s congressional opposition: he summoned Biden for one-on-one meetings to warn him about the changes, spoke out forcefully at rallies for immigrant rights, and organized a call with top White House aides and the Congressional Hispanic Caucus. Padilla, along with four other Democratic-aligned senators, ultimately voted against forwarding the bill, ensuring its collapse because Republicans also opposed it.

“He is a lone voice, but it is a courageous voice in the Senate,” said Vanessa Cardenas, executive director of America’s Voice, an immigrant advocacy organization.

Padilla’s climb has been swift, and those who have known him since his days in California politics will not be surprised. He is now in his fourth year in Congress.

“What he’s always been brilliant at is being able to navigate the space, bring people together, and be a constructive player,” said John A. Pérez, California Assembly Speaker during Padilla’s tenure in the Senate. “With Alex, you don’t get criticism without an alternative.”

Padilla was also recognized as a determined and competent negotiator. While on the Los Angeles City Council, Padilla struck a statewide agreement with then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger to increase funding for local governments. What was supposed to be a one-day meeting became a ten-day, round-the-clock negotiation in Sacramento. Padilla swiftly depleted his wardrobe and had to wash his socks in the sink, according to Mike Madrid, a Republican strategist who collaborated with Padilla on the League of Cities. They received the compromises they desired.

Madrid stated that now that Padilla is involved in the immigration policy debate, “the politics have never demanded border security more and immigration reform less.”

However, he admitted that he could be proven wrong: “If there is any one person in Washington who can make that deal happen, it would be Alex Padilla.”

Padilla sees it as the primary reason he entered politics in the first place.

When he graduated from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with an engineering degree in 1994, his parents’ dreams were realized. His father was a short-order chef, while his mother was a house cleaner. However, he was quickly drawn into politics when the state’s focus shifted to Proposition 187, a 1994 ballot measure that was enacted to restrict education, health care, and other non-emergency services to undocumented immigrants.

Supporters dubbed it the “Save Our State Initiative.” Padilla still remembers the campaign’s advertisements.

“Trying to try to blame a downward economy on the hardest working people that I know was offensive and an outrage,” he told reporters.

He now sees parallels between California in the 1990s, when the ballot measure was enacted but later declared unconstitutional in federal court, and the rest of the country today: changing demographics, economic uncertainties, and political opportunists “scapegoating” immigrants.

It did, however, encourage Latinos in the state to become politically active. Padilla believes it’s no accident that California, the state with the most immigrants, now has the country’s largest economy and is a Democratic bastion.

Padilla’s first political job was directing the state assembly campaign for Cárdenas, who is roughly a decade older than Padilla and grew up just a few blocks away in Pacoima, a San Fernando Valley suburb.

The campaign began as an improbable endeavor by two political novices to get the area to elect a Latino for the first time. Cárdenas recalled Padilla working so hard on the campaign trail that he fell asleep standing up while they debriefed one night.

“We were literally laughed out of people’s offices at the time,” Padilla told me. Nonetheless, Cárdenas won.

Padilla went on to work for the late Sen. Dianne Feinstein and handle several local campaigns before running for Los Angeles City Council at age 26. Padilla advanced fast through the council, reaching president at the age of 28. Padilla oversaw the emergency response for two days after the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, while then-Mayor James Hahn was trapped in Washington. Padilla conducted interviews in both English and Spanish to comfort the city’s residents.

But before being elected to his first office, he was questioned about his age. Cárdenas said his bid for the council seat only took off after Padilla finished a debate with a phrase commonly used in the San Fernando Valley’s hardscrabble community: “No te rajes.” Do not give up.