Fatal Exchange! Revisiting Police Deadly Force Guidelines Amid Controversial Shootings

The shootings of two men on opposite ends of the country this month have refocused attention on police deadly force guidelines, as well as how officers should respond when they see a gun. In both cases, the men were fatally shot while holding their firearms pointing down.

On May 3, “fourth-person” reports of a domestic incident at an apartment complex in Okaloosa County, Florida, led a sheriff’s deputy to the front door of 23-year-old United States Airman Roger Fortson, who was alone in his unit. The deputy’s body camera footage shows him pause to listen at Fortson’s locked door before knocking, waiting, pounding again, and screaming out, “Sheriff’s office, open the door!”

The door opens, revealing Fortson, a skinny African-American man dressed in jeans and standing barefoot on the tiles of his doorway. His left hand is raised in an open-palm gesture, while his right hand holds a revolver. It’s held loosely and directed to the floor. In the time it takes him to open the door, the deputy says, “Step back,” unholsters, draws his gun, and fatally shoots Fortson.

“It wasn’t a good exchange, he never fired a weapon or anything,” says Benjamin Crump, an attorney who represented Fortson’s family and attended the funeral. “He respected authority,” he adds about Fortson.

The Okaloosa Sheriff’s Office initially described the incident as “self-defense,” but the Florida Department of Law Enforcement is now investigating.

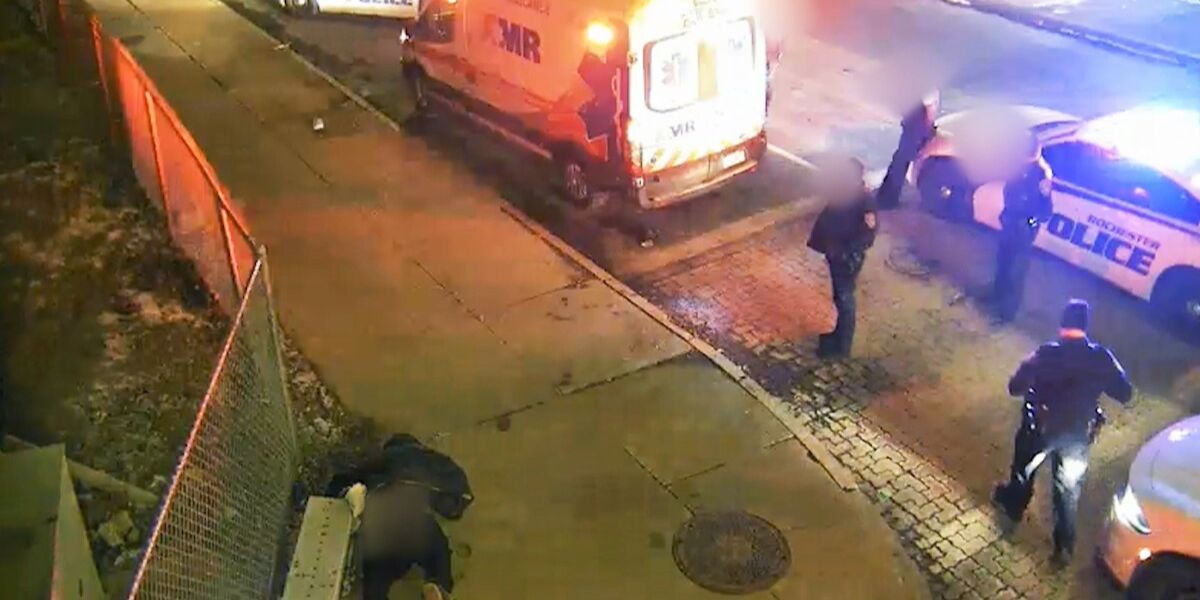

Ten days later, police shot and killed another guy with a gun pointing down while responding to a domestic disturbance call in Anchorage, Alaska. Police Chief Bianca Cross stated the morning after the killing that the guy, Kristopher Handy, “raised the long gun towards officers,” however a video released later by one of Handy’s neighbors seemed to contradict this. It shows Handy outside the apartment complex, approaching authorities with an apparent long rifle held nearly parallel to his legs. Handy, like Fortson, was shot shortly after confronting the cops.

The Anchorage Police Department is investigating, and Handy’s family is requesting the release of body camera footage from the event.

The latest deaths have raised concerns about whether police can shoot someone who is armed but not pointing their weapon.

“There is no hard and fast rule when it comes to that,” says Rodney Bryant, a 34-year Atlanta Police Department veteran, former chief, and president of the National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives.

“Sometimes you may have a person that’s not pointing that still may pose a significant threat to law enforcement officers,” Bryant explained. “But… you can have a very similar situation and it’s clear the person is not a threat.”

No Hard and Fast Rule

What complicates matters for cops is the science of human reaction time. Stephen James runs a lab at Washington State University that investigates this by performing simulations on participants, including police officers. According to these research, police who wait to have a firearm pointed at them suffer a two-to-three-second disadvantage.

“There’s no way a human can see the weapon coming up, make a decision about whether or not it’s a threat, then decide to press the trigger and then the electrical signal has to go from the brain down the nervous system into the finger,” James explains. “If you have to wait for all of that, the other person will get a shot off first.”

Because of this lag, James claims that officers across the country are taught that “action will beat reaction.”

However, he claims that is not a cause to shoot someone brandishing a firearm.

James also participates in state-mandated reviews of police shootings, and he believes officers must follow the law, particularly the 1989 U.S. Supreme Court case Graham v. Connor, which requires an officer’s choice to shoot to be judged by a “reasonableness” test.

“Considering the totality of the circumstances, is the individual acting in a threatening manner? Are they being compliant or defiant? Even the location of the subject could influence whether a shooting is justifiable.

“[In] the case in Florida, it was within reach of his own house. And it is completely protected by the Second Amendment as long as he can legally possess the rifle,” James explains. “It’s very different when you’re out in public … and we don’t allow open carry of guns in schools, for example.”

“It’s hard to train for this,” adds Chief Bryant. He says he’s seen some departments promote research demonstrating the time disadvantage for officers who wait, while others emphasize the importance of backing up and de-escalating a possible confrontation if there is time.

Over the course of three decades in law enforcement, he has observed that police are increasingly encountering this circumstance, particularly as states have allowed open carry. It may take some time for an officer to realize what is going on.

“I’m arriving on the scene, and the person that’s taking the gun from one person — from the volatile person — is there intervening, and I pull up and they have the gun,” Bryant elaborates. “I don’t know who’s who, but I challenge that person as well [to drop the gun],” he replies.

“When you have the proliferation of weaponry that we’ve seen, you just encounter it more,” he continues. “Seeing the gun will be very common, and we have to be prepared for that on both sides.”