Inside the Michigan Heffron Lab that ensures ‘consumers get what they pay for’

In Michigan, consumers can be sure they’re receiving what they pay for when they purchase anything by weight, from beef chuck to gummy bears. The Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development’s consumer protection division, which weighs products and their packaging at the Heffron Lab, is responsible for that.

FOX 2: WILLIAMSTON, MIAll the holiday fare, including beef chuck, fruit cake, a chocolate Santa, and Christmas sugar cookies, is set out in front of Chris McCormick.

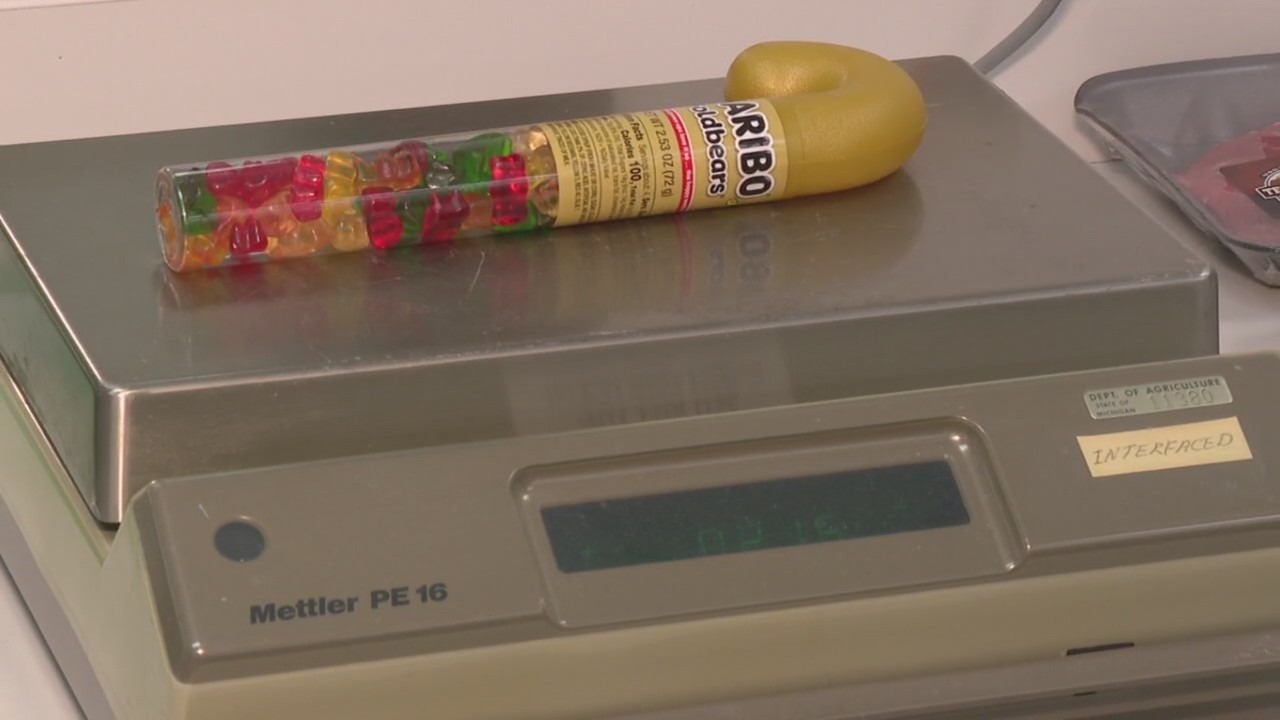

However, some of these products won’t even come out of their packaging by the time McCormick is finished using them, and they aren’t meant for human consumption. He selects a gummy bear-filled plastic candy cane.

The tube was ripped open, and the gummy bears were emptied into a bowl. “We have to do destructive testing,” he remarked.

Although fruity candies are delicious, the man in Michigan’s agriculture department’s Weights and Measures Section is more intrigued by the container they come in.

McCormick discovers, using a scale and some basic math, that this packet of gummy bears weighs approximately 0.166 pounds more than what a customer would pay for.

“So you’re getting more gummy bears than you paid for,” he replied. Furthermore, who doesn’t enjoy receiving additional gummy bears?

It’s possible that Michigan customers are unaware of the hidden checks and balances that make sure they’re getting what they’re paying for, whether it’s fertilizer or pet food, ground beef or bleach, or even gasoline for their vehicle.

The Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development is home to this consumer protection section. McCormick is the metrologist responsible for ensuring that a customer buying a pound of ground beef is actually paying for a pound of ground beef.

This is due to the fact that the fee does not include the cellophane wrap, foam tray, or soak pad underneath the meat. McCormick is responsible for making sure that none of the packaging is included in the weight listed on the package.

“It’s important to get what you pay for, right?” he said.

“We’re making sure things are accurate,” the division’s director, Tim White, stated. “So when you buy gas, when you buy a bottle of pop, you’re confident that what it says is what you’re getting.”

Calibration at the Heffron Lab

The hidden layer of safeguards operates 20 miles from Lansing in an unassuming building south of Williamston.

The Heffron Metrology Laboratory’s remote location was selected by design – away from the vibrations of truck traffic and any other variables that could disrupt their scales.

That’s because even dust particles, grains of sand, or the air blowing from a nearby vent could add milligrams to a scale and give an improper reading.

There are only 36 labs in the country with a weights and measures division for consumer protection. Michigan’s lab has national accreditation and is certified by National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

This ensures that a pound in Michigan weighs the same as a pound in Ohio, guaranteeing a product sold in both states has the same mass. There are also accommodations for moisture loss and temperature change, depending on where things originate from and where they are going.

“It’s like a chain – everything is connected,” White said. “So that everybody is using the same standard, that five gallons of gas is five gallons of gas.”

Fuel pumps are among the most scrutinized in the state, and McCormick says they often have some of the highest compliance rates, while packaged goods fail the most – though he emphasizes most do a good job of ensuring everything is accurate.

“Packaged goods are usually where you find slightly more issues, but most places do a really good job,” he said.

Buying a bag of chips

When McCormick first applied for his job at the Heffron Lab, he discussed a bag of chips – one of the Internet’s favorite punching bags for allegedly ripping off those that buy it.

A vacuum-sealed bag swollen with air and salty chips may be found to have a paltry number of chips, but was it an actual scam?

While the debate over shrinkflation and whether companies are putting fewer chips in individual bags continues, McCormick says that as long as the amount of food labeled on the container is actually inside, the producer is not breaking any rules.

“Maybe they have gone from a 10 ounce bag to a 7 and a quarter ounce bag, but if the bag size is the same, but the weight is lower, they’re (the producer) not lying about how much is in there,” he said.

When McCormick is looking for things to test, he often looks for items with new kinds of packaging he has not seen before or products that are being sold at higher-than-average prices.

If he finds anything short, he works to understand the scope of the issue, who is being affected, and sends that information to management for further instruction.

But as long as companies are not filling a container with less than what is printed on the packaging, they’re in the clear.

“Basically, there is no amount you’re allowed to be short,” said McCormick.

Note: Every piece of content is rigorously reviewed by our team of experienced writers and editors to ensure its accuracy. Our writers use credible sources and adhere to strict fact-checking protocols to verify all claims and data before publication. If an error is identified, we promptly correct it and strive for transparency in all updates, feel free to reach out to us via email. We appreciate your trust and support!